Child psychologists and teachers refer to the intense

learning cycles of extremely precocious and highly motivated children as a

phase known as the ‘rage to

master’ or ‘rage to

learn’. During this time, new, complex skills are attained during an

unusually brief and intense learning phase, and at an unusual and accelerated

rate.

This ‘rage’ is all-consuming, and usually results in a near

perfect and (most importantly) early

mastery of difficult mental and physical tasks that seem far beyond the

abilities of not only ‘ordinary’ children, but their adult counterparts as

well.

‘Rage’ is a good word to describe the single-minded

intensity of this phase in children. I should know, because I was one of them.

***

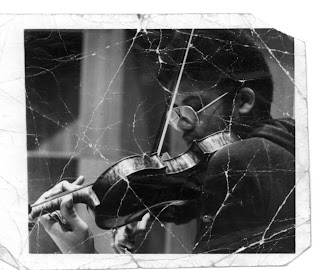

For me, it began during the late summer of 1973. That was

the year I finally persuaded my parents to let me take violin lessons. (I had

seen the movie, Humoresque, starring

John Garfield and Joan Crawford, and had immediately decided that I wanted to

play the violin, and learn the title piece.)

They relented, but only if I agreed to some conditions:

1. I had to stick to it for longer than a few

months.

2. I had to find a teacher they could afford.

3. I had to find an instrument they could afford.

4. I had to practice every day.

Because this was many years before the Internet, I had to

find the teacher and the fiddle by the only means available in those days, the

yellow pages, and free trade newspapers.

For the violin, my parents and I found a place that rented

‘school grade’, instruments by the month for $14.00. Even though that amount does

not sound like much money now, it was a sizable monthly investment on my

parents’ part back then, because they still had eight others in the family to

provide for, including themselves (plus two

dogs) and they had no way of knowing whether I would ‘stick to it’ or not.

I eventually found a teacher in a free newspaper (in those

pre-Internet days) called The Learning

Exchange.

So, with violin rented, and a teacher engaged, the lessons

began. My new teacher was imminently patient, and warned me that, as new

students go, I was already ‘a bit too old’, (at age 16) to be starting a new

instrument, especially one as supremely difficult to master as the violin. When

I told him I wanted to be a ‘virtuoso’ and play like the lead character in Humoresque, (John Garfield’s Paul Boray),

my new teacher smiled patiently and said, “We’ll see. . .”.(The actual fiddle parts

of the soundtrack were laid down by none other than the late Isaac Stern, who,

at the time, was my favorite violinist.)

At the time, neither my teacher nor I even knew how far I

was willing to go to pursue this near unobtainable goal.

Fortunately for me, I did not have to wait long to play Humoresque by Dvorak. A simplified version of it was

available in a beginner’s collection from the old Lyon & Healy Music Store,

which used to sit at the corner of Jackson and Wabash in downtown Chicago, only

a block away from where I took my lessons.

Lyon

& Healy was right across the street from another music store of bygone

days, Carl

Fischer. I used to frequent each, right after my lessons to browse sheet

music, and look at instruments.

Fortunately for me, there was also a Rose Records

store a few blocks north of those two stores, down on Wabash and Adams, where I

used to also go to browse through albums and cassette tapes. Across the street

from Rose Records was a Kroch

& Brentano’s bookstore. Between all

those establishments, almost right in the middle was a Central Camera store (still there), which

I used to window-shop for my photography hobby. For quite a long time, that

little two block-by-one-block area was all that I knew of, or cared to see of

Chicago’s downtown.

Like the boy in the movie (Robert Blake as the child Paul

Boray), I practiced religiously daily after school, and on Saturdays after my

violin lessons. And, like that character, I even practiced when my brothers and

sisters ran outside to play with their friends.

My parents were not completely

caught unawares by my sudden, intense dedication, because they had all seen

it before with my artwork, my writing, and my fascination with the space

program, AND my fanatical love of books and reading. I also use to keep what I

used to call my ‘observation’ notebooks, filled with scientific notes and

sketches, mostly of the local flora and fauna, and ‘stuff’ I dissected.

Still, playing the violin, because of the noise it made throughout the house, was

a different thing altogether, because now, everyone in the family had an

inescapable, front row seat to my growing obsession to learn and master that

most difficult of instruments. They could not have avoided that sound if they

wanted to. As anyone who has ever heard a beginning violinist attempt the

impossible task of scraping music out

of catgut and steel, they probably wanted to escape at some point.

Yet they did not have to wait long for my playing to

improve. After a few months, I was playing Vivaldi (A Minor Violin Concerto),

and simplified versions of orchestral excerpts and famous violin solo pieces, such

as Brahms’ Hungarian Dance #5

and Czardas by Monti,

typical student fare, albeit for someone with a few more years experience

playing than I had at the time.

In fact, I practiced the violin so much, and in so many

rooms of the house, the ‘culture’ of the violin somehow infiltrated the family

lingo. I once heard my brother say to one of my sisters, who had been continuously

calling him to get his attention, “That’s

my name! Don’t turn it into a concerto!”

I kept my violin lessons a secret at school because I did

not want anyone to know about it (in case I failed or flunked out at it), and

because back then, our school had a band, but no orchestra, so it did not

matter anyway. Even then, I had the habit of keeping the various aspects of my

life strictly compartmentalized, a habit I retain to some degree to this day.

I played, practiced, and took lessons throughout the rest of

that summer, and into the winter, the spring, and finally the next summer (1974)

between my junior and senior years in high school.

***

Something strange happened when that summer, the summer of 1974 started, and school let out. I did

the opposite of what my parents fully expected me to do, once school was out

and all the kids of the neighborhood were free to run and play with no cares

for almost three months. (Actually, my

summers had never been filled with running and playing, more with reading books

and comic books, going to the library, drawing, and occasionally visiting with

one or two friends of like mind.)

For reasons that escape me now, I suddenly vowed to practice

ten hours a day to master the fiddle so I could be a ‘real’ violin player when

school started again. All my other summer activities were put aside.

This seemingly innocent, impromptu decision is how the rage

began in earnest for me. Once it started, it was so intense, so all consuming,

so mentally and intellectually mesmerizing that on my own, I would have never noticed

the passage of time, the beginning or ending of the day, the need for food,

water, or sleep. If not for my parents, my dog, and my siblings, I would have

foregone all bodily needs and functions (all

of them), merely to practice all day until my parents were ready to ‘shut

down the house’, for the night. Then I grudgingly went to bed, exhausted. The

next day, it started all again, for an entire summer.

·

I set upon a strategy and a seemingly impossible

task, I would practice ten hours a day all summer, so I could audition for the

All-City Orchestra when school started, then play violin in college after

graduation later that year (1975).

·

(As

previously mentioned, our school had a band, but no orchestra, however, I would

still need the band instructor’s permission to audition for All-City Orchestra,

which consisted of only the best high school students from top Chicago high

schools, the ones that could afford to have an orchestra. The competition was

stiff, with students who had played their instruments much longer than I had

played mine.)

·

If there were ever a time that my parents realized

I was different, this was definitely one of them. (In retrospect, I am certain

they already knew, from the compulsive behavior I showed for my other

interests, which were growing in number every year.)

·

I arose at 8:00 every morning so I could have

two whole hours to get my chores done, and take care of my dog Damon.

·

I started practicing at 10:00AM, and would stop

only for short breaks (at my parent’s insistence), meals, and walks for Damon. The

daily sessions would last until 10:00PM every night, with no weekends off. (Sometimes

I could to get one of my brothers to walk my dog Damon.)

·

During my breaks, I would lie on my bed and read

'The

Glory of the Violin' by Joseph Wechsberg, or peruse sheet music of

stuff I wanted to play. Sometimes, my best friend would come over and try to

get me to come out of the house. He usually gave up after a few minutes, and

would leave frustrated, but only after hitting my right arm attempting to knock

my bow from the strings. (I also recovered playing with little or no

interruption.)

·

I started each session with scales, then etudes.

Then I practiced orchestral excerpts, short encore pieces (nothing too

difficult, mostly pieces by Kreisler (Liebesleid and Liesbesfreud) and the

Beethoven Romances),

and the Vivaldi A Minor Violin Concerto, and ‘advanced’ student concertos by Mozart (3, 4, 5), Viotti, Vieuxtemps,

the Bach E Major Violin Concerto,

and Lalo (the first movement of Symphonie Espagnole).

·

Next I spent at least 3 hours practicing some of

the ‘less difficult’ Bach Sonatas

and Partitas, followed by more etudes, scales, book reading (to rest my

arms and shoulders), and ‘forced’ meals. My dog Damon would come into the room occasionally

to visit. Sometimes, he would stay, and sleep at the foot of my music stand,

and sometimes he would get bored, and walk away. (I have since found that cats seem to tolerate the harmonics of violin

music much better than dogs.)

·

The summer ‘raged’ on until school started. By

that time, I had sustained a ten-hour a day practice schedule through rainy

days, hot and humid days, holidays and summer barbecues, and family functions,

which I skipped one and all. I developed muscle sprain, soreness and tension in

my upper back and shoulders, knotted hand muscles, and a dark bruise under my

chin and on my clavicle from holding the violin. My fingertips had calluses

from playing double-stops, and sliding along the fingerboard hundreds of times

a day, and I temporarily developed blurred vision.

However, it all resulted in the desired outcome, because

soon after school was back in session, I was easily able to earn a spot in the

second violin section of the All-City Orchestra, beating out students from

other schools who had started to play their instruments ten or more years before

I began my lessons. Because I was from a school without an orchestra, I

realized I was representing our entire music department, and I wanted to do

well.

***

In end, when I reflect on my so-called ‘summer of rage’, I

realize that, as unusual as it may have seemed to some, it was a look forward

and a preview of how I, even today, tackle all such big problems and projects,

and how that ‘rage to master’, has never left me. It has merely been tempered

by the adult need to have a job and other adult obligations (and other

interests), and, of course, a social life.

It's possible that the phenomenon occurs with the young in part,

because they have none of those obligations (other than a few family chores

from which they may even be excused) and can dedicate most if not all their

waking hours single-mindedly honing and mastering a skill, or several of them.

***

Once, several years ago when my parents were both alive, I

asked them about that summer and what they thought of it at the time. Their

response was that, even thought it had been somewhat unusual to them, it had

also been actually considered typical for me, and not the first time I had done

something like that. (Apparently, and unknown to me at the time, I did it every

time I discovered a new skill or hobby, such as with my writing, my artwork, my

photography, and my tinkering and building, and the notebook keeping and dissecting.)

***

The rage to master and learn never goes away merely because one

gets older; it reawakens every time there is a new skill to learn, especially a

new hobby, or something so intriguing it switches that rage on to full burn.

The difficult part, for me, is turning it back off again.